IEPI BLOG – COVID-19 Boosters: Are we boosting global vaccine inequity and prolonging the pandemic?

Written by Nga Dang

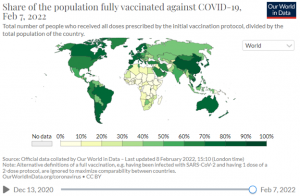

Early in September 2021, my 81-year-old grandmother was waiting to be called by the local public health unit in Hanoi, Vietnam, for her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. At the same time, 80% of adults in high- and upper-middle income countries had already received at least one dose. Over the past few months, my grandmother has received two doses as part of the primary series currently prescribed by the vaccine manufacturers’ protocols. However, billions of people less fortunate than my grandmother, most of whom live in low-income countries (LICs) in Sub-Saharan Africa, are still waiting for their first dose. With only 11% of the population currently vaccinated with at least one dose, many LICs are still working to provide first doses to front-line workers and at-risk populations, let alone the general population. The global COVID-19 vaccination gap is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Fully vaccinated proportions by countries as of February 7, 2022 by Our Word in Data

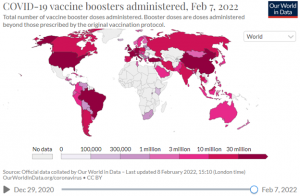

This disparity is now amplified by the mass rollout of third, and even fourth doses in many high-income countries (HICs) and middle-income countries (Figure 2). In addition to acquiring booster dose supplies, the G7 and European Union countries will have secured close to 1.4 billion doses in surplus by March 2022, even after accounting for primary and booster vaccine coverage in 80% of adult populations.

Figure 2 Total number of vaccine booster doses administered as of February 7, 2022 by Our Word in Data

A WHO simulation model on the world’s supply of COVID-19 vaccine in 2021-2022 emphasizes the visible gaps between supply and required doses in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) if boosters are broadly used, even when risks associated with manufacture, technology transfer, scale-up and one billion doses donated by HICs are taken into account. Although Africa had received over 474 million doses as of December 30, 2021 through the COVAX initiative, the Africa Union vaccine acquisition scheme, and bilateral deals, at least twice this number is needed to fully vaccinate 40% of people living in Africa. As the WHO aims for 70% coverage of COVID-19 vaccination by mid-2022, Africa may not reach this milestone until 2024. Therefore, mass rollout of COVID-19 boosters amid shortages of first doses in many LICs, especially sub-Saharan African countries, raises both scientific and ethical questions about the global allocation of limited resources.

The Science

Many HICs, including Canada, France, Germany, Israel, the UK, and the US, began offering booster doses to the general population as early as October 2021, when the majority of people in LMICs had not received their first dose. The rush to roll out booster doses partly reflects reports of breakthrough cases among fully vaccinated individuals and signs of waning vaccine efficacy suggested by recent studies. However, these preliminary signals, often framed in the news as a sign of weakened vaccine protection, warrant additional research. Vaccinology questions remain, such as what the optimal vaccine combination, schedule, dosing interval, and measures of protection are.

Increasing vaccination coverage is expected to raise the number of breakthrough cases, simply by proportion – even with highly effective vaccines, breakthrough cases are to be expected, and with a greater number of people vaccinated, more breakthrough cases will be reported. Behavioral changes among vaccinated people, such as less physical distancing and not using masks in public, also contribute to upticks in breakthrough cases. Critically though, while breakthrough case numbers are rising, risks of severe disease and death are greatly reduced with widespread vaccine coverage and are more concentrated among people over 60 years old with chronic diseases and compromised immunity than among the general population.

Previous studies on the primary vaccination series found slightly eroded vaccine effectiveness against infection but still high protection against severe disease, hospitalization, and death (1, 2, 3). Among recent studies comparing the effectiveness between primary series (i.e., all doses currently prescribed by the manufacturers’ protocols) and booster doses, only three report on clinically meaningful outcomes (i.e., disease severity, hospitalization, and mortality). Two analyses from Israel and the UK suggest that the primary vaccination series might not provide as much protection against severe disease, hospitalization, and death, as previously believed, especially with the spread of highly infectious Delta and Omicron variants. These reports, however, are based on observational data collected over short periods (i.e., two weeks and 10 weeks), and may not account for important confounding factors that influence the direction and magnitude of effects (e.g., behavioral differences by vaccination status; regional differences in prevalence of variants etc.). A recent report from the US found similar patterns during Omicron-predominant periods. While vaccine efficacy decreased, it was still close to 60% against hospitalization for those vaccinated with the primary series for more than six months.

In assessing the evidence from these studies, we need to make a clear distinction between protection against infection and protection against serious disease. No currently available COVID-19 vaccines completely prevent individuals from being infected with SARS-CoV-2. While some studies report a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies over time, it is still uncertain if these antibodies correlate with immunity against COVID-19, as long-term protection also relies on memory cells. Even scientists whose research suggests a correlation (between immunity and antibody levels) believe that while protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection may decline over time, protection against severe disease should retain.

Since the goal of COVID-19 vaccines is to prevent people from developing severe symptoms that require hospitalization, which would cripple health systems, these vaccines are doing exactly what they were designed to do. Moreover, infection in fully vaccinated individuals usually leads to asymptomatic or mild disease, and hospitalizations and deaths are largely driven by unvaccinated individuals. Although widespread use of booster vaccinations may offer additional protection, meaningful and sustainable control of the pandemic can only be achieved by vaccinating the unvaccinated.

New COVID-19 variants will continue to emerge among individuals who are not yet vaccinated (1, 2). In regions where the majority of the population has low immunity, the virus may be incubated with the potential to multiply on a large scale. A greater chance to multiply means a greater chance to mutate, and mutated strains (variants) may develop properties that make them more transmissible, more virulent, or both. Thus, not only will new variants emerge, but new variants that are resistant to vaccines may also follow. In this case, variant-specific boosters may be recommended; and if this strategy is prioritized among people who are already vaccinated with primary doses, resources would be further diverted away from unvaccinated populations in LICs, potentially leading to an infinite cycle of new variants.

The Ethics

Ideally, the global COVID-19 vaccine supply would be distributed fairly and equitably, as consistently advised in ethical guidance by international health organizations (1, 2) and global health ethicists (1, 2). On a global scale, COVID-19 vaccines should be initially allocated to populations with highest priority to maximize the benefits of such a scarce resource, before expanding to the broader public. Although guidelines differ with respect to definitions of populations with highest priority, in general, there is consensus that frontline and other essential workers (e.g., medical personnel, custodians, personal aides, transit operators, grocery store employees, etc.), and those at risk of developing severe disease should be prioritized across the world.

These global prioritization frameworks, while ideal, are often at odds with individual countries’ obligation to protect the wellbeing of their own citizen. However, even when state obligations seem to justify widespread distribution of booster doses, there is a moral threshold that limits the extent of national priority in the context of a global pandemic. Emanuel et al. argue that once the risks of death from COVID-19 resemble those of more common infections like seasonal influenza, hoarding limited global vaccine supplies for domestic use cannot be ethically justified. In other words, if COVID-19-related mortality is maintained at a non-crisis level (i.e., level of expected death pre-COVID-19) with reasonable public health measures, countries still have the responsibility to share vaccines with those in crisis.

Currently, more than 60% of the general population in HICs have received the full primary vaccination series, and many HICs are easing strict lockdowns and resuming near-normal activities. In recent months, excess mortality levels in some of these countries have been brought down close (i.e., within 20%) to recorded mortality levels in the same period before the pandemic between 2015 and 2019. This suggests that increased sharing of COVID-19 vaccines with LICs, where the pandemic burden is highest, is urgently needed and ethically responsible.

The Bottom Line

Emerging evidence suggests some waning vaccine efficacy against infection over time, and states have an obligation to protect their residents’ well-being. However, additional studies with more robust designs are needed before broad policy changes are implemented. Furthermore, there is a moral threshold to national priority, and plans to introduce booster shots to the public before people in LICs receive their primary series may be premature and potentially prolong the pandemic. What all countries need to do now is to take the collective responsibility and treat COVID-19 for what it is: a global health crisis that requires equitable solutions for all.

Acknowledgement

I thank my colleagues, Kristy Hackett, Matthew Grellette, and Claudia Emerson, for their expertise and feedback in writing this blog.

Blog, Infectious Disease Management, Nga Dang